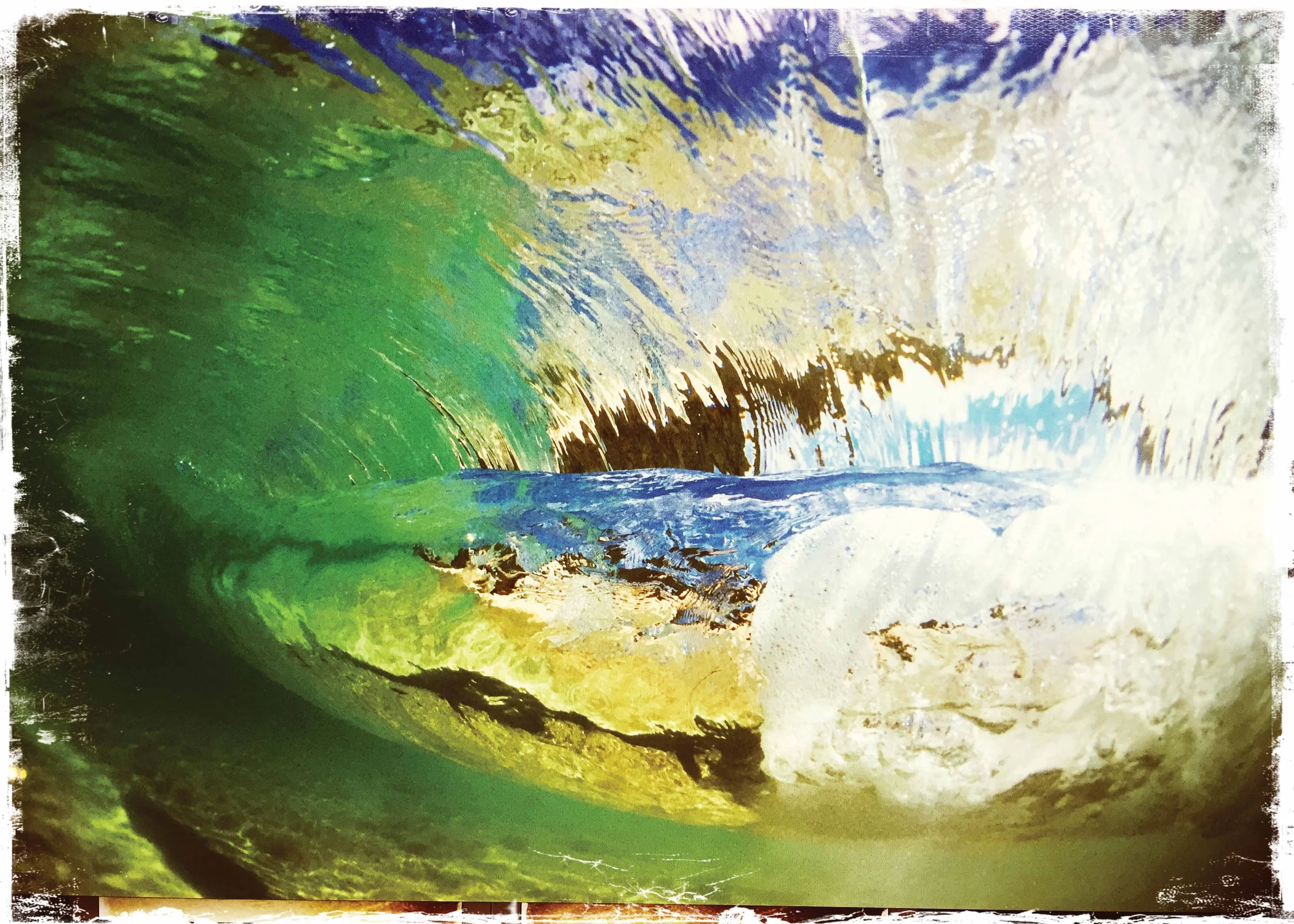

Swell Sight

View From Under by master surf photographer Sylvain Cazenave. (All photos courtesy Sylvain Cazenave.)

On winter mornings on O‘ahu’s North Shore, the Pacific Ocean often changes imperceptibly: the water tightening, horizon thickening, birds flying lower and closer to shore. For decades, Sylvain Cazenave learned to read these signs the way others might read newspapers.

A storm thousands of miles away, he knew, born in the North Pacific and driven east by winter pressure, could already be on its way. Four, maybe five days out. Before arriving without warning as 20-foot walls of water at Pipeline.

Cazenave, one of the most influential surf photographers of the last half-century, has spent his life studying the waves. Paddling towards danger with a camera pressed to his chest, Cazenave captured sprawling images of sunlit barrels and figures dwarfed by the sea, his work helping define how surfing entered the global imagination. But the man himself always preferred to remain outside the frame.

“I never wanted a story about myself,” Cazenave says. “I tried to stay behind the lens.”

Ready for the Pipe by Sylvain Cazenave.

Learning Surfing by Sylvain Cazenave.

Scrambling Up the Face at Waimea Bay by Sylvain Cazenave.

Born in Lille, France, but raised in Chad, Congo, and across central Africa (where his father moved around for work), Cazenave and his family eventually settled near Biarritz on the Basque Coast. He began surfing as a teenager. This was the late 1960s, when the sport barely existed in France. “No more than a hundred people were surfing,” he remembers.

The few who did came from far-off places such as California and Hawai‘i. These strangers fascinated the young Cazenave, who learned English as a way to talk to them and ask: Who are you? Why do you surf, and why here? At home, his father subscribed to Life magazine and National Geographic, where the world arrived weekly in glossy pages. Cazenave wanted to visit the places he saw. Photography, he later realized, was a way of traveling without leaving.

“But there was nothing in France” at the time, says Cazenave. “No surfing magazines, no [commercial] photo industry, nothing.” Instead, he took odd jobs like cleaning swimming pools to pay for his photography equipment and film. In the mid ‘70s, Jeff Divine, then a photographer, and eventually the photo editor of Surfer magazine, looked at Cazenave’s work. Your pictures are good, Divine told him. Why don’t you become a photographer?

The timing was perfect. Windsurfing was suddenly exploding in popularity across Europe. Brands such as Quiksilver and Rip Curl emerged internationally almost overnight. “We all grew up together,” Cazenave recalls. “I was a windsurfer too and right there when these sports were getting very big in France very fast.”

Shooting first with a Nikonos camera (based on the Calypso, the first self-contained underwater camera designed by Jacques Cousteau), then a 35mm camera sealed inside a custom waterproof housing, Cazenave began selling his images to magazines as well as to a growing advertising world eager to appropriate surfing’s allure. “A bank decides to show a wave so they use my pictures. Or someone’s selling washing machines or soap and they want frothy water,” he laughs.

Cazenave’s first visit to Hawai‘i came in 1980. For surfers and photographers alike, the North Shore was a proving ground. “There was Hawai‘i, and then there was the rest of the world,” says Cazenave. “Everybody talked about Hawai‘i. And by Hawai‘i, I mean in between Hale‘iwa and Sunset Beach, what they call the Seven Mile Miracle.”

Waikiki Longboard Rack by Sylvain Cazenave.

Moving Longboards Around by Sylvain Cazenave.

Low Tide At La Cote by Sylvain Cazenave.

Sylvain Cazenave at his namesake gallery in Biarritz, France.

There were only three or four photographers in the water at Pipeline back then. “We could all be in the water, nobody would be in the way of each other’s photos. On the beach was the same.” Every day, they would shoot rolls of richly saturated Kodachrome 64, drive to the Kodak processing lab on Kapi‘olani Boulevard and wait for prints.

“When you first learn photography, you take whatever [photos] you can take. But we knew the big names, like Gerry Lopez, and other surfers. And of course they would catch the best wave of the set,” Cazenave says. “So you have to wait for the set, try to be in the right position when the wave is coming, try to be in focus, then shoot.”

Weather forecasting wasn’t as exact as it is today. Swells were often predicted by rumor and intuition. If Cazenave’s friends in Japan said there was snow one day, that meant swells might arrive four days later in the Islands. “Snow means low pressure. Low pressure is going to mean waves are coming.”

He studied the tiny weather maps in the pages of the Honolulu Advertiser and sought out knowledge from local experts, like renowned surfer George Downing, who taught Cazenave how to read the ocean the old way: by watching clouds, currents, birds, and shorebreak.

“The Hawaiian people were sailors and lived on fishing. They understood the waves. Lots of them knew how to read the ocean and the weather,” says Cazenave. “I learned a bit more. Even though I didn’t have the perfect forecast, I could understand what was happening. Why a swell was two feet in the morning but 20 feet a few hours later.”

Cazenave used his new skills for the next 40 years as he chased waves around the globe. Hawai‘i in winter, then Indonesia, Australia, Morocco, Peru, South Africa, Scotland, Brazil, and beyond. Assignments rolled in from magazines and agencies; Cazenave’s images appeared everywhere from Sports Illustrated to Playboy. In the 1990s, his work took to the air when Cazenave began shooting from helicopters alongside a young Laird Hamilton, capturing the birth of big-wave tow-in surfing from a perspective few had ever seen.

In time, more photographers, surfers, and spectators flooded the beaches, putting added pressure on coastlines. “You touch the water and you feel it’s different,” Cazenave says. The crowds, as well as pollution and development, were having an impact. “There is plastic everywhere and grease on the ocean. Even when they throw all the garbage away, you see the color of the water.” Cazenave became involved with Searider Foundation Europe, founded in Biarritz to help protect the ocean. He also became a husband and father, opening a gallery in Biarritz to display work that magazines had once rejected for being too “artistic” for commercial use.

“People come to the gallery and say, ‘30 years ago, in 1992, you went to Germany to that windsurfing contest and you photographed me. Do you remember?’ And yes, I usually remember. We sit down and talk,” says Cazenave. “I have somebody who helps me run the gallery because I like to meet the people.”

Cazenave still returns to Hawai‘i. He still keeps an eye on the horizon, though he no longer feels compelled to catch every set as he did when he was younger. The waves come when they come.

“I love Pipeline but I can’t swim there anymore. When I turned 50, I felt on top of the world. When I turned 60, eh…” Cazenave says, rocking his hand side to side in a “so-so” gesture. “I just turned 70 years old two years ago. I now think, even if I want to go to Pipe, don’t do it. Every time I see waves eight to 12 [feet], I think: Yes, I could do it. But no, no, I cannot… But maybe?”

Cazenave thinks about it. “My daughter is here for three weeks so the priority is family,” he declares.

“Unless the waves are insane. If you tell me Pipeline is going to be all-time tomorrow, I will say to my wife and daughter: I love you. But tomorrow you won’t see me. I’ll be at Pipeline.”

Tehaupo’o Tahiti by Sylvain Cazenave.

Summer Swimming by Sylvain Cazenave.

Learning Swimming by Sylvain Cazenave. (All photos courtesy Sylvain Cazenave.)