Signs of the Times

FROM THE 10TH FLOOR OF THE 12-STORY ATLAS BUILDING, NEAR THE INTERSECTION OF KING AND PENSACOLA, ARTIST KAMEA HADAR’S VIEW IS FAR-REACHING.

He’s a hundred feet above Honolulu, standing outside on a suspended scaffold called a swing stage, the one typically used by window washers. On the horizon, Hadar can see the rooftops of assorted warehouses and commercial buildings where his large-scale murals of eyes, faces and figures have become ubiquitous throughout the city in recent years, and something of a personal trademark. He can see Kaka‘ako, the shapeshifting urban corridor between Ala Moana Center and downtown Honolulu, where he and high school pal Jasper Wong first organized a weeklong, mural-painting event in 2010 that has since grown to become POW! WOW!, the outdoor art festival held each year in a dozen cities around the world, from Long Beach to Tel Aviv to Hong Kong. And below, Hadar can see the cars slowing down on King Street as drivers peer up to watch him work on his latest mural.

Up here, just about the only thing the artist can’t really see is, well, the artwork.

“You can’t really trust your eyes because the platform is three feet wide. So there’s no stepping back for a better look,” Hadar says with a laugh. “Maybe you think you’re drawing a perfectly horizontal line. Then, when you get down, you see the line is drooping six feet or so. That can happen when you’re working on something that’s 100 feet across.”

Luckily, sketching helps. Hadar uses pencils or markers to map an outline of his image before he starts painting. He’ll often number the floors using blue painter’s tape on the side of the building to keep track of how high up he is. (Which is impressive, considering Hadar has a fear of heights.)

To maintain his sanity, Hadar employs a grid system: Draw the design on a piece of paper overlaid with, for example, 1-inch squares. Then, scale up the squares to correspond to the size of the building. One inch on the paper becomes 10 feet on the wall, and so on.

“Some structures have windows and gutters that help as visual markers. Other buildings are made out of those standard CMU bricks that are always 8 inches tall by 16 inches wide, which means there’s already a natural grid to work with,” says Hadar. “It’s about using whatever references you’re given.”

Other than that, he has to trust his instincts, honed over the past decade as one of Hawai‘i’s most accomplished muralists. A Kalani High School grad, Hadar studied at Honolulu Academy of Arts (today, the Honolulu Museum of Art) and the University of Hawai‘i before further developing his skills at the Sorbonne in Paris, Saint Louis University in Madrid, and University of Tel Aviv in Israel. A mastery of the essentials — such as visual framing and creating smooth, clear lines — is especially critical for the piece he’s painting on the side of the Atlas building, which isn’t an ethereal face but a series of letters, each roughly 20 feet tall. “VOTE!” it proclaims. “YOU RUN 808.”

It’s a mural with a message: Local people should be stewards of these islands, so Hadar is encouraging the importance of voting because Hawai‘i traditionally has the lowest voter turnout rate in the United States, ranking dead last in both the 2008 and 2016 presidential elections. Amazingly, Hadar will finish this roughly 70-foot-tall mural in less than 48 hours, though it’ll only be up for four days.

“A lot of people love the piece for what it was, a nonpartisan mural calling for voter turnout. There was no secret agenda; the goal was to give people hope and let them know the power is in our hands as voters. But the artwork also caused a lot of backlash and people got very creative in their criticism,” Hadar says. “Some people thought it was a billboard because there were words on it. Other people complained it was an advertisement for the Runner’s Route, a shoe store, because of the word, ‘run.’ I don’t know. I’m a little sad that I eventually painted over the mural, but I’m proud that at least the piece got such a strong reaction and it started a discussion.”

Coincidence or not, Hawai‘i would see the largest voter turnout ever recorded the following month, with 51 percent of registered voters in the state casting their ballots this past August.

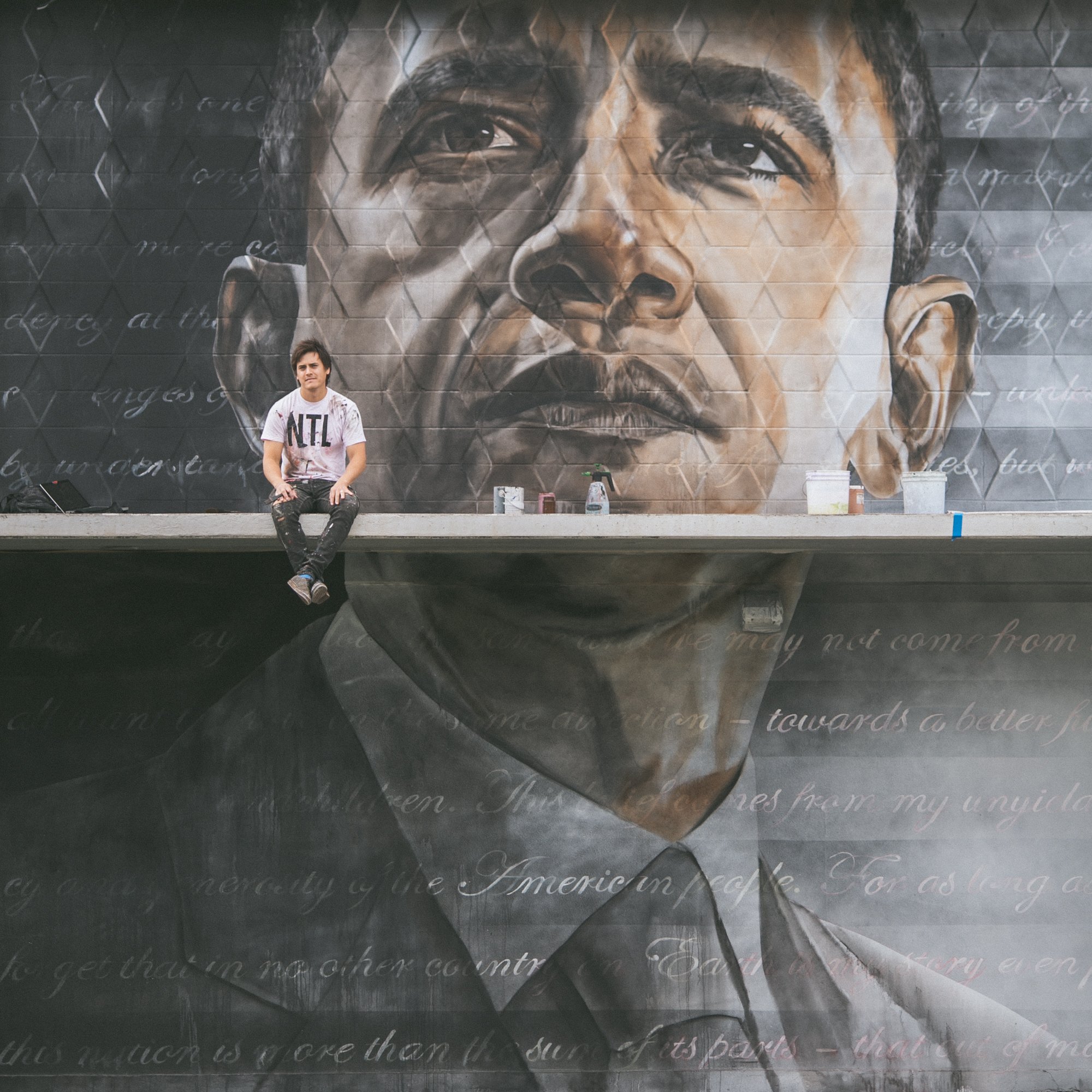

Hadar is used to his artwork attracting eyes and making an emotional impact. Drive down Ward Avenue, and you’ll see Hadar’s handiwork on the Gary Galiher Law Building, where a commanding visage of Barack Obama looks out over the city in which the former president was born and went to high school. This 2016 mural, Hapa, was the result of a conversation between Hadar and the late Galiher about creating imagery to celebrate racial diversity (Galiher’s daughter is of mixed ethnicity) and Hawai‘i’s melting pot culture.

Step aboard the USS Arizona Memorial or the Pearl Harbor Visitor’s Center and look east to catch a glimpse of Hina (short for Hina-‘ai-ka-mālama, the Hawaiian goddess associated with the moon), painted to commemorate the 2017 homecoming of the sailing canoe Hōkūle‘a and the completion of the historic, worldwide circumnavigation voyage, Mālama Honua. In a pose similar to the Statue of Liberty — with a lei po‘o (head lei) instead of a metal crown and holding taro, one of the earliest canoe plants the ancient Polynesians first brought to Hawai‘i, instead of a tablet — Hina is the tallest mural in the state at 165 feet (and 14 feet taller than Lady Liberty).

“A lot of my paintings are inspired by Hawaiian imagery because this is where I’m from. I painted landscapes before I got into human forms and portraiture. Recently, I’ve been creating lots of florals,” says Hadar. “I’m constantly evolving and learning. I think you have to be able to go with the flow as an artist because that’s the nature of the game.”

In recent months, part of Hadar going with the flow has been in response to COVID-19. “In the past, I once went on something like 27 paintings trips in a single year,” Hadar muses. “In 2020, of course, everything’s been cancelled.”

Although painting murals is technically considered “essential” under the umbrella of construction work, Hadar has shifted his focus from outside to indoors — creating commissioned works at his home studio where the artist can also spend more time with his wife, Shanna, and their two young children. From September to November, he also partnered with Treehouse Coworking in Kailua to help organize Coping with COVID, an exhibition of works by local artists inspired by the coronavirus quarantine.

“Artists — and not only in the visual arts, but also writers, musicians, performers, and creatives in general — are on the forefront of society’s voice. [For example,] when you listen to music from the 1960s, you have a window into what they were going through at the time,” says Hadar. “Images, stories, and sounds being created now are documenting this period in time. The art of today will let people of tomorrow see what we saw. Or what we hope to see.”