Framing the Story

I’m that person who’s been drawing and painting since I was 5 years old,” says Justine Stamen Arrillaga, whose passion for art started at a very young age. Perhaps her passion for altruism came into being a little later, but most recently, they came together for one very special solo exhibit — the first for the 52-year-old, Honolulu resident.

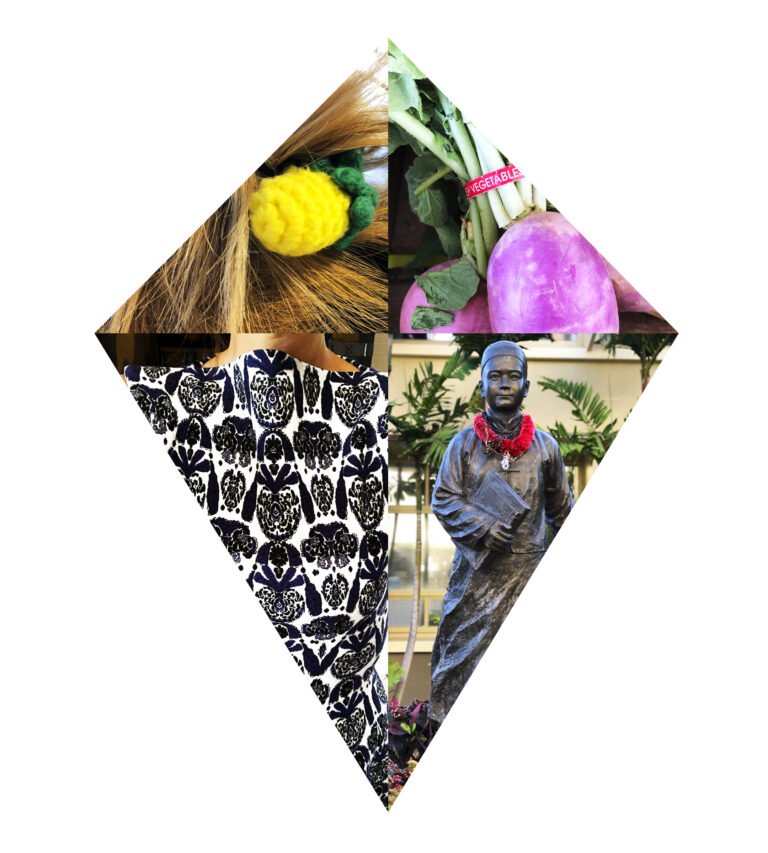

Ka Lele Paheona (Flying Art) — a series of 13 kites created by Stamen Arrillaga — comprises a selection of curated photos shot by her and those of her dear friend, Pat Hammond. While each kite symbolizes different experiences, the series depicts a common thread they both share — their lives and love for Hawai‘i. The exhibit debuted in late February in San Antonio, Texas where Pat is from and currently resides; here in Honolulu last March; and in Los Angeles (where Stamen Arrillaga hails from) this April. Aside from the 13 works in limited editions of 10, Stamen Arrillaga also created five, special-edition NFT kites. “I thought it’d be kind of neat to have kites flying around in that atmosphere,” she jokes.

While the project from start to finish may have taken two years to finish, the seeds for Ka Lele Paheona were planted more than two decades ago in a humble basement in New York City. Back in 1998, Stamen Arrillaga founded the nonprofit TEAK Fellowship in honor of her best friend, Teak Dyer, who was attacked and murdered in Los Angeles the night before their high school graduation in 1988; and DeWitt White, a music prodigy whose life was also cut short when he was killed at 17 years old in 1997. The two tragedies compelled Stamen Arrillaga to start the TEAK Fellowship. And it was during that time that she met Pat (now 84), who was visiting son Robert — co-founder of the now famous High Line — who Stamen Arrillaga was already friends with.

“He was trying to start the High Line and I was trying to start TEAK, and it was unclear who would be less successful because everyone thought we were crazy,” Stamen Arrillaga shares. “I wanted to send low-income, high-achieving students to the top 40 prep schools in the Northeast and then to the most established universities in America. He wanted to build a park on a broken-down railroad that would extend miles over New York City’s west side.”

Inspired by Stamen Arrillaga’s mission and vision, Pat offered to teach art for TEAK and showed the students how to make kites for several summers. “She was this magical, Mary Poppins-like lady from Texas, with spinning tops in her pocket, collections of lace and she even collected words,” recalls Stamen Arrillaga.

The two continue to remain in touch, and during the start of the pandemic, Pat discovered a treasure trove of slides containing photos taken during her time in Hawai‘i when her husband, Hal, was stationed here in 1959. A lover of photography, Stamen Arrillaga too, had amassed quite a collection of photos since she moved to the islands almost nine years ago. She immediately begged Pat for the slides so she could take a look. She was amazed.

“I took them to Treehouse [Photo Lab] and they printed these slides for me. The images were so clearly shot in a different time but in the exact same neighborhoods that I’ve been in for these past years.”

Stamen Arrillaga doesn’t combine Pat’s images with her own though. Seven of the kites are filled with Stamen Arrillaga’s pictures while six are made up of Pat’s. Upon inspection — or maybe introspection is the better word — one can already tell if a kite is a “Pat” or a “Justine.” Nuances of color, tone and subject style all give hints to when each photo was taken. She says, “These images are from Pat’s and my daily lives, separated in time…”

For Stamen Arrillaga, these kites represent hope and her own journey flying over to Hawai‘i; it represents the TEAK Fellows and how far each of them has gone in their own lives; and a tribute to her friendship with someone who has always encouraged her to fly high.