Pole Position

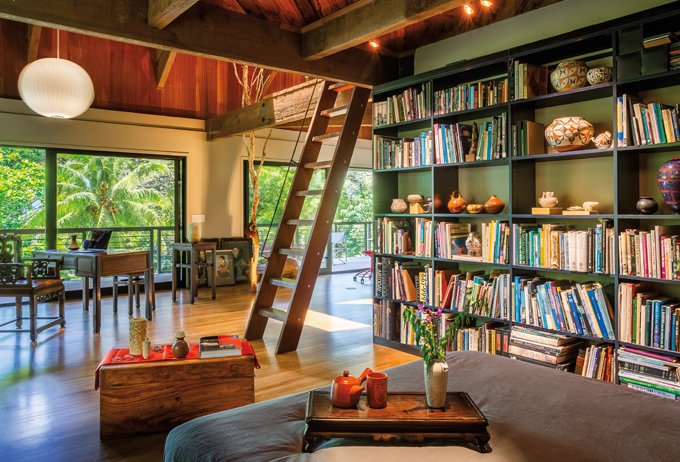

In the lush green valley above Nu‘uanu Stream on O‘ahu, Hawai‘i Architect Alwyn Trigg-Smith faced a conundrum: how to revitalize and connect (literally and figuratively) three separate houses, two of which had fallen into disrepair nearly to the point of disintegration. What’s more: These weren’t just any three buildings. These were several of Hawai‘i’s original pole houses: spacious, open-air parcels suspended 15 feet above the ground atop freestanding wooden columns.

“It’s always easier to build a brand new house,” Trigg-Smith says. “Taking an aging structure, and making it come to life is tricky. You have to change and rework the space, while still embracing what the house was originally.”

For years, Trigg-Smith’s client, a fine art painter, lived and worked in the upper house, while the other two buildings remained unlived in. The railings and balustrades were crumbling, the roof and eaves had rotted away, and gaping holes appeared in the floorboards, where one could peer through and see the forest floor below.

“I’ve grown up with a fear of heights, so I would never even walk through the lower house,” Trigg-Smith says. “I was too freaked out by the fact that in some areas, you could look down and see daylight!”

But what began as a challenge soon evolved into an opportunity to combine contemporary design aesthetics, such as minimalist features and recycled materials, with a historic home of timeless natural beauty.

“The idea became that my client could use the upper house as the kitchen and living room, but the bedroom would be in the lower house,” adds Trigg-Smith, who bridged the properties through a covered concrete walkway.

Structurally unsound sections of the two dilapidated buildings were demolished and rebuilt, but 20-foot-long slabs of redwood, some from species which are no longer commercially available, were salvaged and incorporated in the restoration. The eaves were rebuilt using rustic cedar, while the floors were replaced and reinforced.

Natural elements were integrated whenever possible—for example, using dense, termite-and moisture-resistant Brazilian teak for the outer decks and carport—while modern elements, such as steel handrails and columns, were blended in for support and as a visual accent. The handles of the cabinets in the kitchen and bathrooms were painted the same dark gray to match the look of

metal and concrete.

“For quite a few years, there’s been a ‘new’ type of quartz on the market called neolith. I haven’t done a natural stone counter for some time because this modern material has the feel of quartz, but you could literally take a hammer and chisel and still not make an impact. It’s that strong,” Trigg-Smith says, explaining his use of the modern exception to the rest of his natural materials.

To create the home’s angled carport, concrete columns were made to match the type of poles that the house itself is built on. “We decided to leave these unpainted because it felt more natural,” says Trigg-Smith. “Speaking of color, it’s unusual for me to suggest a house be painted a deep Chinese red, but it wasn’t overbearing on this property, so that’s what we went with.”

Between the staggered walkway and the red exteriors and yellow interiors, there’s a certain playfulness to the home’s new design. But for Trigg-Smith’s client, who prefers to paint and practice his craft everywhere, from his desk in the study upstairs, to the spacious living areas to outside on the terrace, the eclectic style is perfect.

“The way this gentleman works and the way he approaches this house is that he never wanted to be limited to one space,” Trigg-Smith says. “It’s his philosophy to find different places to think and work.”

Venting skylights were added to allow for more natural light into the home in addition to the wide rolling doors. At night, the columns dotting the walkway perimeter of the home are lit and glow cool white.

“Air flow was also critical to ensure this home amid the tropical foliage, could catch the breeze. I also wanted to open the space so every part felt as connected to the outside as possible; to invite nature in,” Trigg-Smith explains.

How do you combine three separate homes? For architect Twigg-Smith, the secret was discovered through exploration: by playing with the idea of shape and volume and adding complementary features to strengthen the house’s existing infrastructure.

“It wasn’t about fighting to add design features, it was about coming up with something different that was still in the spirit of the home,” Trigg-Smith says. “The goal was, you walk out of one house, down to the other house, but you still feel connected to the home—and to nature around you.”