Post-Game Recap

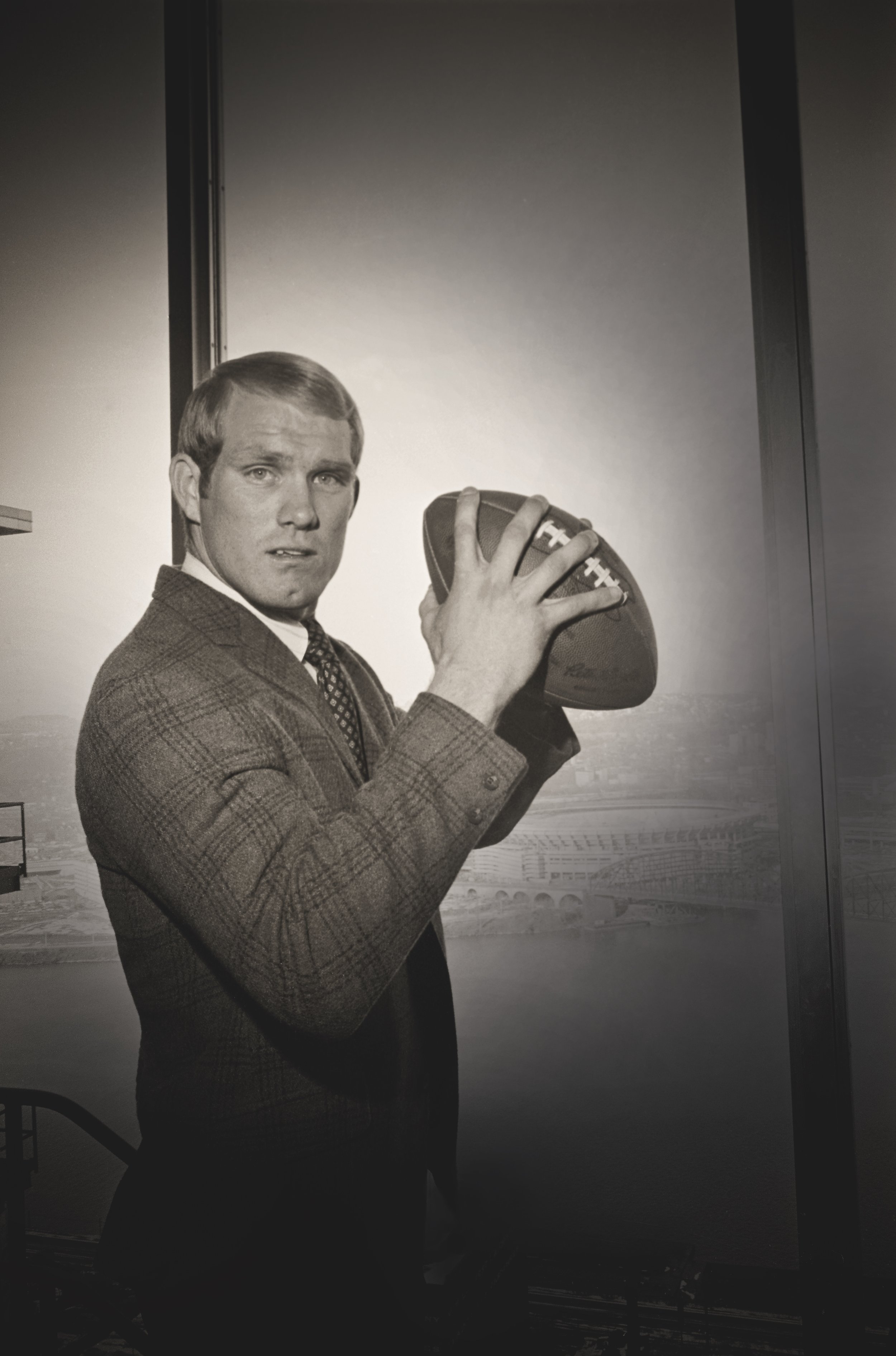

Hall of Famer, sports analyst and TV personality Terry Bradshaw’s Titan-like accomplishments on and off the field make waves.

Terry Bradshaw has a point to make, so he dims the light on his 1,000-watt smile and lowers by a half-step the voice that has commanded titan-sized men on the gridiron, charmed consumers in movie theaters and supermarket aisles, and held the rapt attention of generations of Fox NFL Sunday viewers.

“I always say I don’t want to leave this Earth without making an impact,” he says, a blonde-crested brow furrowing. “I just can’t imagine wasting my life, and all I did was win four Super Bowls and do a reality show, and work for Fox …”

The premise is barely past his teeth before the irony kicks in.

“OK,” he says, “That sounds like a lot. But what have I really done? At 73, what can I do?”

Bradshaw leans back in his chair and lets the questions breathe for a moment.

He’s staked a comfortable perch for a bit of reflection. The skies over the Kohala Coast are clear, and the mid-afternoon heat is moderated by a steady flow of northeasterly trade winds: great conditions for the 18 holes of golf Bradshaw has planned to deliver him into the early evening. He lifts, then sets back, a tumbler of bourbon without taking a sip.

The enormity of Bradshaw’s accomplishments cannot be so casually dismissed.

Football came first and, perhaps, most naturally. At Woodlawn High School in Shreveport, Louisiana, Bradshaw led the football team to a berth in the state championship game and also set a national track and field record for the javelin throw. At Louisiana Tech, he led the nation in total yardage (2,890) as a junior and graduated as the consensus top prospect in

the country.

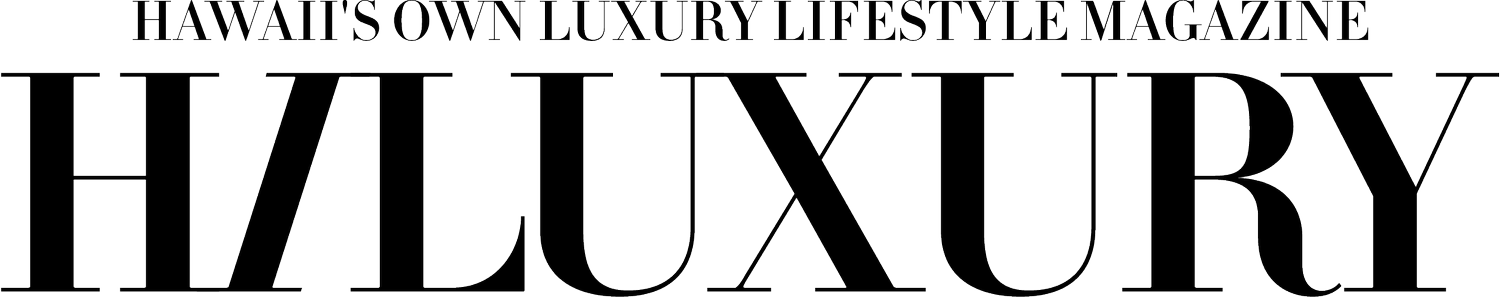

But as No. 1 overall pick by the Pittsburgh Steelers in the 1970 NFL draft, Bradshaw struggled to gain his footing in the league, as jokes stereotyping his Southern roots and supposed lack of intelligence soon followed.

For Bradshaw, who had struggled with undiagnosed Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) throughout his childhood and adolescence, the jibes cut particularly deeply and contributed to problems with anxiety and depression that themselves would go undetected for decades.

I learned through playing football and dealing with critics that this is the dark side of it, so how do I handle it?? Bradshaw asks. ?I deal in laughter, and I’m mostly a positive guy, so I buried myself in the humor and tried to hide some of the hurt. I had to protect myself.

The image Bradshaw projected in postgame interviews on Sunday and Monday nights and how he conducted himself in his daily life were not terribly different. Bradshaw is quick to laugh, quick to put others at ease, quick to make fun of?himself. In that way, he taps into a certain Southern tradition of allowing others to underestimate the brooding intelligence that lies beneath the keep-it-light exterior.

It wasn’t long before Bradshaw’s gifts — powerful arm, poise and an innate sense of the big moment — were unlocked by the hours of practice, study and preparation he invested in his early professional years. In an era when defense and the running game were the understood foundations of championship football, Bradshaw’s leadership and deep-ball threat supercharged the Steelers rushing attack and Steel Curtain defense, leading to the franchise’s first Super Bowl victory in 1975 … and another the following year.

He repeated the feat in 1979 and 1980, becoming not only the first quarterback to win back-to-back Super Bowls, but also the first to do it twice. Along the way, Bradshaw was recognized with one league MVP and two playoff MVPs.

In the years that followed, Bradshaw leveraged his fame and telegenic personality into scores of advertisements, TV appearances, films, even country music albums. In 1994, he joined Fox as an analyst and co-host of Fox NFL Sunday, quickly establishing himself as a straight-talking source of game insight, deeply informed opinion and occasional controversy.

At the close of each season, Bradshaw leaves football behind and heads to Hawai‘i for rest, relaxation and renewal.

“I first visited in 1972 and hosted a tour of all the islands,” the 73-year-old NFL Hall of Famer recalls. “I’d never been here before, but once we landed in Hilo the people were so sweet, and the beauty of the island was just so incredible, I absolutely fell in love. I’ve been back every year since.”

What started as a couple of weeks a year in hotel rooms and vacation rentals eventually evolved into season-long stays with family and friends at a series of luxury properties Bradshaw has bought and sold over the years, including a plantation-style home built on 12 acres of land at Kohala Ranch in Kamuela and a 2,111-square-foot apartment at the Mauna Kea Resort located along the 11th fairway of the Hapuna Golf Course.

It was at the Kamuela property in 2014 that Bradshaw married Tammy Alice, following a 12-year courtship. Last year, the couple renewed their vows, with a full family surrounding them, in an oceanside ceremony officiated by Tammy Bradshaw’s daughter, Lacey.

The renewal ceremony was the centerpiece of an episode of the second season of The Bradshaw Bunch, the family’s reality TV show on E! At Bradshaw’s insistence, the show eschews contrived drama for a lighthearted, honest depiction of the family’s everyday experiences. And while Bradshaw’s personality looms large, it’s his family — Tammy, daughters Rachel, Erin and Lacey, sons-in-law Scott Weiss and Noah Hester, and grandchildren — especially granddaughter Zurie — who have all but stolen the show.

“We said from the beginning that we’re not going to do anything that isn’t us,” says Hester, a Hawai‘i-based chef.

“We eat together, laugh, cry together sometimes. There is no B.S.

Hester, who was tapped to be co-owner of Bradshaw’s recently purchased restaurant in Texas, has become integral to Bradshaw’s expanding business empire.

At Bradshaw’s behest, Hester helped to develop Bradshaw Ranch Thick & Juicy, Bradshaw’s grocery line of frozen hamburger patties. He’s also closely involved in promoting Bradshaw Bourbon, which launched two years ago.

Bradshaw’s foray into the bourbon business came when he started selling autographed bottles of Four Roses to raise money for wounded soldiers. He was interested in starting his own line but wanted to make sure it was a “serious” bourbon and not some generic celebrity-branded whisky. He worked with master distiller Jacob Call of Green River Distilling to develop a proprietary yeast blend that produces a smooth, deep, 103.8 proof bourbon that Bradshaw sells in a classic longneck bottle “like the kind they had in Gunsmoke.”

Bradshaw has further extended himself into men’s attire with a line of clothes inspired by the style and comfort of classic comfort brands like Sansabelt and Ryan Michael. Bradshaw said he favors “Fat Boy Britches,” but the line will likely sell under a tamer brand name when it hits stores this spring.

These are heady, happy days for Bradshaw, a stretch of hard-earned contentment that might have eluded him, had he not also put in the work to address mental health issues that had plagued him his entire adult life.

Bradshaw suffered anxiety attacks as far back as his playing days, and he continued to experience anxiety and severe depression even as his post-football life took off in a dozen enviable directions. By 1999, following his divorce to third wife Charla Hopkins, Bradshaw was in full crisis.

“I went to a doctor’s office and begged for a shot,” he says. “I was an emotional wreck. I was just bawling. I said, ‘Can you give me a shot? Anything? Just knock my ass out for two months.’”

Thus began an intensive three years of Bradshaw reckoning with his accrued traumas, working through emotions long suppressed and identifying triggers that initiate his most intense emotional responses. The right regimen of therapy and medication eventually brought peace of mind and a newfound sense of strength and well-being.

For Bradshaw, the next step had to be sharing his experience in hopes of helping others. He talked openly about having ADHD and living with anxiety and depression. He shared what it was like to undergo counseling and confront hard truths. And while mental health professionals and others welcomed his advocacy, the reaction from those steeped in the hyper-masculine culture of football was decidedly mixed.

“I had good friends laugh at me, and that was tough,” he says. “There is still a stigma that depression is a sign of weakness. People don’t understand that it’s a disease. They make fun of it because they don’t understand, but they don’t realize the impact their statements have on people who are struggling.”

Attitudes have evolved over the last 20 years, in part because Bradshaw and others braved the ridicule to normalize the discussion of mental health within amateur and professional sports. Bradshaw said he was encouraged by the response to Olympian Simone Biles, when she withdrew from competition after struggling psychologically.

“Not knowing anything about gymnastics, I know that fear and depression sets in, and especially when you think about all the people that love you, your sponsors, and you feel like you let them down,” he says. “The best thing that happened was when her greatest fear became her greatest support. That was cool. I thought her support group was phenomenal.”

Bradshaw is enamored of his own support system, anchored by his best friend and wife, Tammy.

“She knows when my body is starting to struggle or my mind,” he says. “It feels so good to be sitting on a rocker, on a patio by yourself, and then someone puts a hand on your shoulder and says, ‘Are you OK? What can I do [to help]?’ Well, you just did it.”

Bradshaw said people come up to him wherever he goes and thank him for sharing his experiences with depression. Former and current athletes have also reached out, confidentially, to ask questions or to share their own struggles. Perhaps, he thinks, this is the answer he’s been seeking.

“I don’t want to leave this world just as a football player or announcer or whatever,” he says again. “But maybe, I’ve helped people who aren’t strong enough yet to know that it’s OK…”

The words linger in the humid air. Bradshaw shrugs, regards the final finger of bourbon in his glass.

“Life is good,” he says, finally. “I’m a blessed and happy man.”