Match Up

The year was 1988 and it was the party of the decade.

More than 1,100 people filled the tents outside the Black Orchid, a glitzy new restaurant at the also newly opened Restaurant Row. Hundreds more were lined up on South Street to get a view of the guests, including Magnum P.I. stars (and Orchid co-owners) Tom Selleck and Larry Manetti. Former Honolulu Star-Bulletin dining columnist John Heckathorn was also on the scene, “sweating in an ill-fitting Sears rental tux, wondering just whose idea it was to hold a black-tie party outdoors in July.”

Heckathorn, who politely asked Selleck to quit blocking the way to the buffet table, later interviewed Randy Schoch, another Black Orchid co-owner and local Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse and Macaroni Grill restaurateur, about the birth of the restaurant, and its ultimate closure four years later.

“Selleck and Larry (Manetti) weren’t really owners ... We just gave them some stock to use their names,” recalled Schoch in a 2008 article. “Larry would do stuff like order Louis XIII [cognac] at $150 a shot and then put it in his Coke, which we had to talk about.”

After Black Orchid got sold in 1992, it became an Italian restaurant named Rex’s Black Orchid, then Sansei, Hiroshi’s, and Vino. More than 30 years later, there’s no trace of what was once the hottest destination in Honolulu. No website, of course, but also almost no surviving press. Besides a couple photos of Selleck and the other owners floating around on the web, there are also no images of the Black Orchid; no way to know what the place even looked like or proof it existed at all.

But there is a matchbook.

For all the attention that the restaurant received during its heyday, a 2-inch white box with “Rex’s Black Orchid” printed on the side is all that remains to carry on the legacy. More than a souvenir, this little matchbox has become Hawai‘i history itself.

“Matchbooks are a unique link to the past because they sometimes might be the only reminder of a certain time or place, especially in an era before the Internet,” says Donna Blanchard, who originally started collecting matchbooks from restaurants she loved. “More than half are closed now but the matches help contain the memory.”

Blanchard can appreciate the significance of collecting pieces of the past as a way of preserving people, places, and cultures. Originally from Chicago, she’s the managing director of Kumu Kahua Theatre, the only theater in the United States solely dedicated to presenting original plays that relate to a specific geographical region.

“It’s what I call ‘theater of place,’” Blanchard says. “Plays about life in Hawai‘i, written by Hawai‘i playwrights, for the people of Hawai‘i. That’s our motto.”

Kumu Kahua has been sharing local stories for more than 50 years. The theater organization was founded in 1971, amidst a renaissance of Hawaiian culture in the Islands. It was a time when visitors walking down Kalākaua Avenue could hear live music spilling out of the International Market Place, at hotspots like the Cock’s Roost — a steak and ribs joint where Carlos Santana occasionally performed before rising to fame in the late ‘60s — or Trader Vic’s, Hawai‘i’s “original Polynesian” restaurant. (“Trader Vic” Victor Jules Bergeron, Jr.’s friendly competitor, Ernest Raymond Beaumont Gantt, a.k.a. Donn Beach of Don the Beachcomber, built the original International Market Place.)

Across the street, the colonial-style Moana Hotel has been hosting guests since it first opened in 1901. In 1932, the hotel sold for $1.6 million to the shipping company Matson, which also operated the Royal Hawaiian, Surfrider ,and Princess Ka‘iulani hotels as elegant accommodations for tourists who traveled to Hawai‘i aboard Matson luxury vessels, such as the Lurline, Mariposa, and the Monterey.

By the mid-1930s, the Moana Hotel’s Banyan Court achieved fame as the recording studio-of-sorts for Hawai‘i Calls, a live radio show featuring local performers, like Alfred Apaka, Benny Kalama, and Hilo Hattie. From 1935 to 1975, Hawai‘i Calls served as an audio postcard that brought authentic Hawaiian music, as well as “the sound of the waves on the beach at Waikīkī,” to the West Coast and middle America.

“I’m always surprised to meet local families with Blue Hawai‘i-type memorabilia. I always assumed it was just what the tourism industry decided to make Hawai‘i seem like to be more friendly for people like me, originally from the midwest,” says Blanchard.

Radio producer Webley Edwards hosted Hawai‘i Calls for the program’s nearly 40-year run; previously the station manager at KGMB, Edwards was the only broadcaster to witness both the beginning and end of America’s involvement in World War II. He first announced that Pearl Harbor was under attack on the morning of December 7, 1941 (“This is no exercise ... All Army, Navy, and Marine personnel to report to duty”), and was the chief announcer for the surrender ceremony aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945.

Life in Hawai‘i changed as a result of World War II. For Sadako Kaneshiro, who was Japanese but born in Waipahu, it meant a whole new name. “During the war, we have to have [English names] legally,” recalled Kaneshiro in a 2002 interview with historian Michiko Kodama-Nishimoto. “My English name, my teacher gave it to me at Wai‘anae [School]. She was a haole teacher, and then she gets hard time calling us Japanese names ... She gave my name, ‘Beatrice.’ I said, ‘okay.’”

In 1941, Kaneshiro and her husband, Fred Toshio Kaneshiro, opened the first Columbia Inn near the corner of Beretania and River Streets in Chinatown. The casual diner quickly became a hit among locals. These included retired Japanese wrestlers, American servicemen who preferred Columbia Inn’s breakfast to the powdered eggs they usually ate on ships — “Normally you order ham and eggs, like two eggs, right? They used to order six … and milk by the gallon” — and prostitutes who worked in a brothel above the restaurant. “They come downstairs, pick up the food, and take them up,” Kaneshiro recalled.

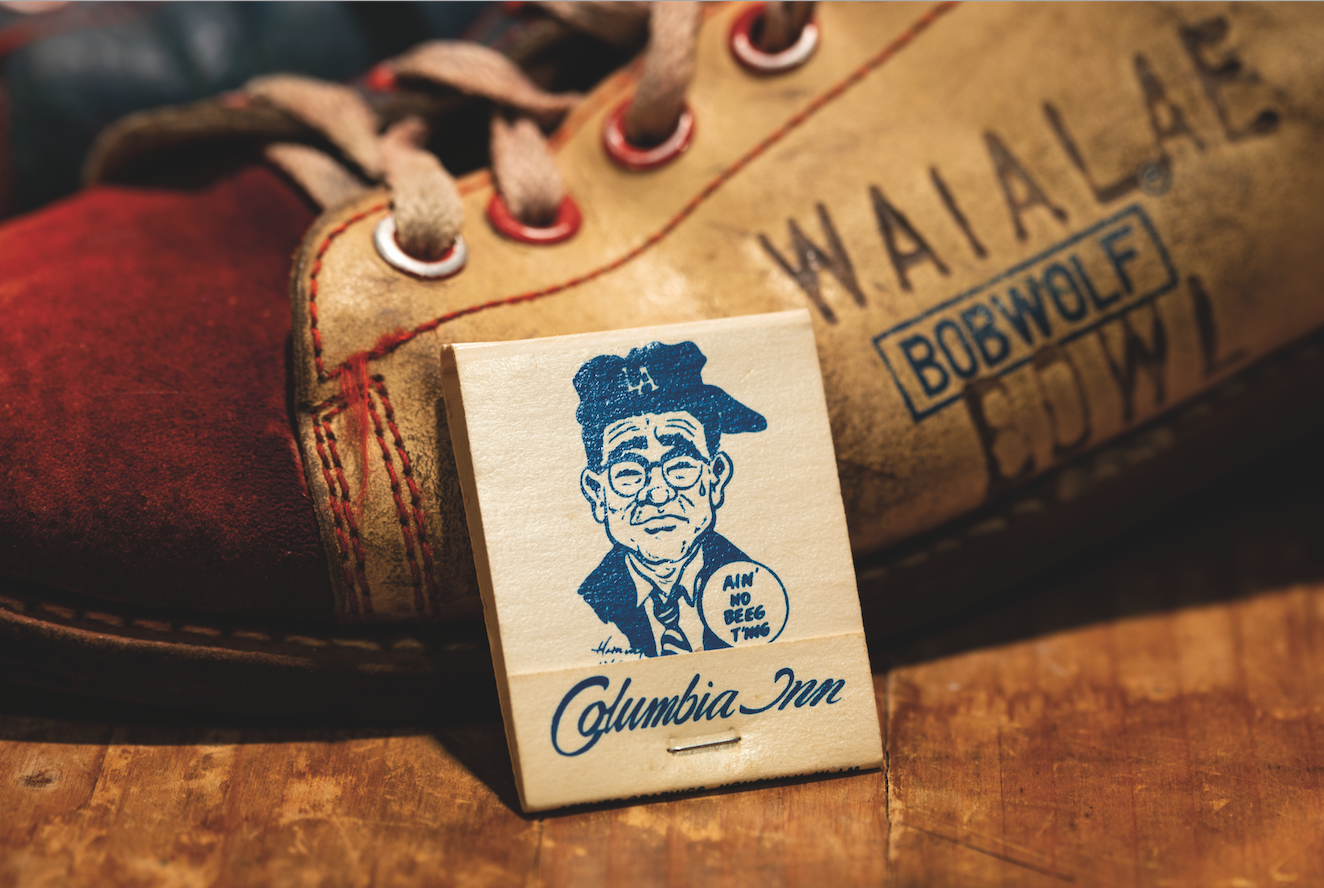

Honolulu Advertiser cartoonist and Columbia Inn regular Harry Lyons knew Fred Kaneshiro was a baseball fan and sketched the owner’s likeness, complete with a Dodgers cap and pin reading “AIN’ NO BEEG T’ING” (a catchphrase from Hawaii Five-O). The Kaneshiros liked the illustration so much, they put the image on the restaurant’s matchbooks.

Open for nearly six decades, Columbia Inn was among a pantheon of comfort dining institutions in Hawai‘i, including Like Like Drive Inn, Wailana Coffee House, and the Pagoda “Floating” Restaurant — where illusionist David Copperfield first got his start, performing sleight-of-hand magic at the Pagoda’s adjacent C’est Si Bon club at age 19.

“They gave me my first gig ... to hone my skills and work on my chops in front of terrific audiences — in beautiful Hawai‘i, no less — [and it] was a dream come true,” recalled Copperfield in a message at the Pagoda’s 40th anniversary celebration in 2004. “Nothing is quite like the rush I got from working at the C’est Si Bon for the Hayashis.”

“Depending on when you were born, matchbooks are souvenirs and a way to look back,” says Blanchard. “But if you weren’t around, it might also be the only way you can learn about a particular place or subculture or history. That means something.”