Hidden Figures

Any conversation with a passionate collector is akin to whitewater rafting on the Colorado River — one surrenders to the meandering flow with its rushes and excitement punctuated by placid moments and languid eddies that spin off into uncharted forks that reconnect further downstream. And when the collector’s knowledge of every piece’s creation and provenance is as voluminous as Michael Horikawa’s, the conversation cannot be anything but just as thrilling of an experience.

The headwaters of this conversation began with a mere burbling brook of an idea to share a few seminal pieces from Horikawa’s collection of carvings and figurines, representative of the earlier art being produced in the late-19th century through the late 1960s. While the entire collection spans decades more, and continues to be added to through the present, he is keenly passionate about certain artists and sculptors from that era.

A seasoned curator of notable museum-grade exhibits, Horikawa’s process was on display as he freely shared the relevance of each piece as they were considered not just for inclusion, but also relative to each other. The editing process of determining which pieces to share was not easy, given that museums regularly inquire with him about the possibility of including notable items from his various collections in their upcoming exhibitions. Listening in and trying to capture it all is like trying to snatch a sip of water from a fire hydrant as the flow of information comes from all sides; but there is a certain joy in surrendering that task to a digital recorder and just having Horikawa’s passionate thoughts flow unhindered as they envelop us.

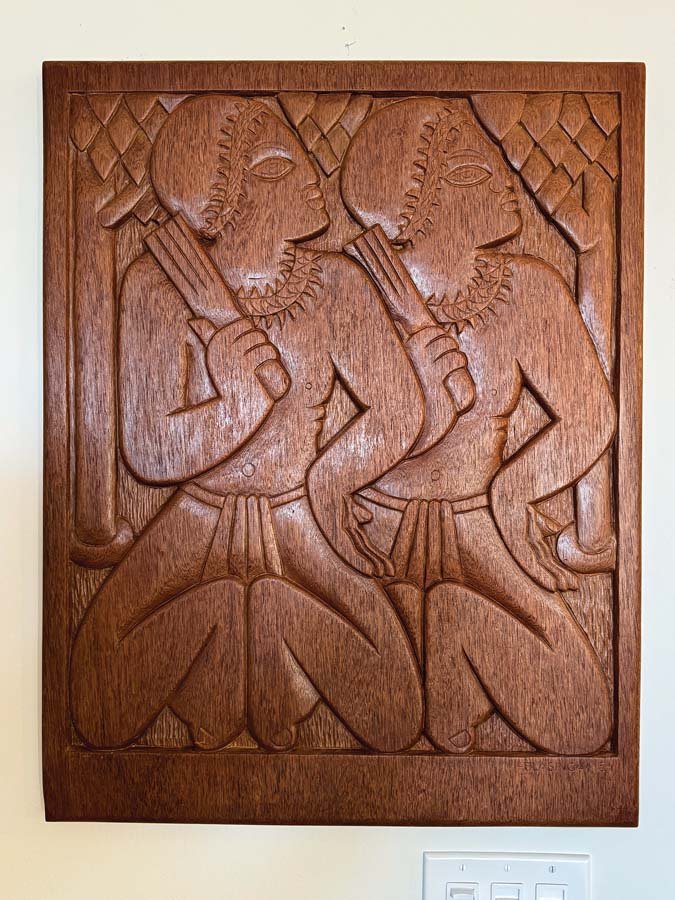

“Let’s start with Otremba,” Horikawa decides. “Frank Otremba. Wait, Frank, originally Franz Nikolaus Otremba, born in Germany and trained in Europe before coming to Hawai‘i in 1882. Yes, he would make a good starting point, because while there were certainly earlier and prior examples of sculpture in Hawai‘i, his work is recognizable as being from one of the earliest masters to come to Hawai‘i in the early 1880s,” he adds. The piece is a square koa wood plaque with a hanging bunch of mangoes carved on the bias and meant to hang diagonally as originally displayed for sale. Like all the pieces that we would see during our visit, it would not be out of place in a gallery today; even a layman’s eye can connect the many dots since then until today’s carved wood treasures. “Otremba carved a bust of King Kalakaua,” Horikawa mentions as a part of the artist’s bona fides, “but he also carved retail art. This would have hung in a gallery on Fort Street.” We carom onwards with the reminder that artists were always intrinsic to society and that art created for sale or commissioned by patrons, has been a constant for millennia.

But before we jump too far ahead, a relatively diminutive tangential object in metal by Kate Kelly takes us briefly off course, and this is the beauty of unscripted conversation: it brings up more names and pieces to be noted later on as the examples evolve from carved sculpture to figurines.

“I could go on…” is a frequent refrain during our visit when the knowledge is spouting from a virtual card catalog of knowledge, “but let’s move along.” And thus, we follow our guide. There is no bucking the current once in it, and the names are peppered like islands in the stream; “Let’s talk about Abplanalp and his decades of influential work.” Picking up speed, one senses that the rapids are approaching: “Ok, Fritz Abplanalp, you can look up his family’s story, he was Swiss, born in 1807 and came to Hawai‘i in ’35 to carve for S & G Gump, one of America’s original luxury retailers. We know of only about 200 existing perfume bottles like this pair here. And interestingly, he carved every single one personally,” Horikawa says, holding out a priceless example displaying the finely filigreed fronds of a fern, complete with its fiddlehead cap.

“His influence on the genre is outsized among his peers; this here is a bust carved from a piece of driftwood that Abplanalp came across while on a walk on a West Side beach, and in it, he saw the form of a face.” And with that, we take in the bust that birthed a genre whose adherents continue to this day; the carved driftwood that reveals the finely honed surface of the subject’s face while leaving much of the natural live edge and rough-hewn remnants of the found object. Included in the collection from the hand of the master carver are examples made during the artist’s tenure at Kamehameha Schools where he rounded out his career when the war disrupted sales at Gump’s.

Another gravity drop comes with the revisiting of a previously spied figurine resembling a trophy-topper. “This one is by Kate Kelly — oh! One actually became the iconic hood ornament on Duke’s car — but then as a result of failing eyesight, she ended her work and supported the art career of her husband, John Kelly… but let’s save him for a future article.” Horikawa mentions all this with the ease and familiarity of someone who likely knows exactly where and when the legend himself affixed the sculpture to his automobile.

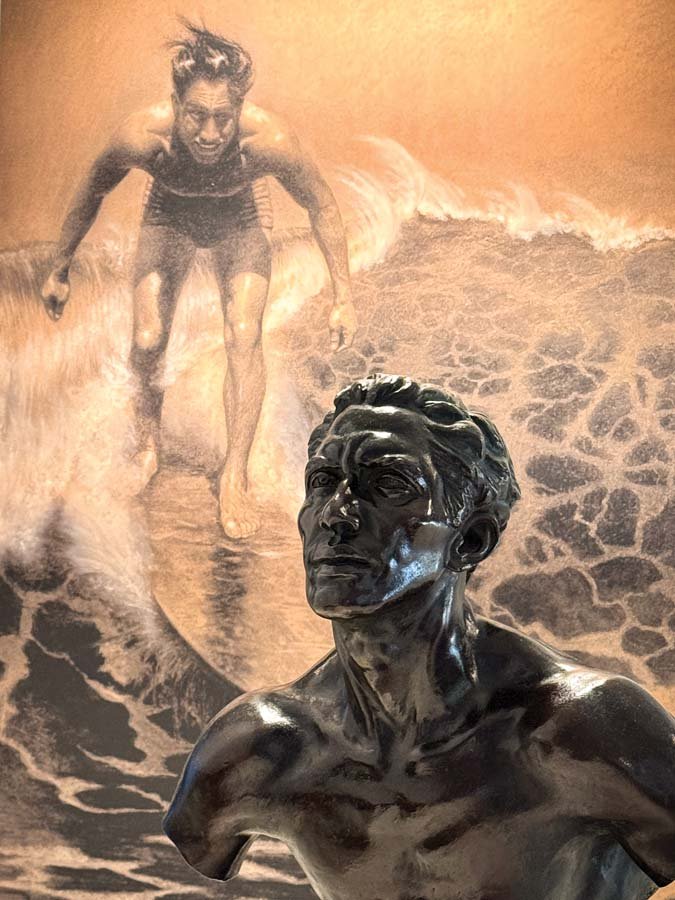

From there, we pivot headlong into works by Malvina Hoffman and her depictions of notable Hawaiian individuals. A bronze bust of Sargent Kahanamoku is revealed. “This is the study for the full-size bronze commissioned by the Field Museum in Chicago, and Duke didn’t want to sit for Hoffman, so Sarge did.” And Horikawa can’t help but playfully juxtapose the bronze with a poster from the Mid Pacific Fair in the background, showing Duke on a wave. Hoffman’s work spanned the Pacific and notably depicted cultures from the islands and into Southeast Asia, serving as one of the art world’s first records of indigenous statues and carvings made using western practices such as plaster and bronze casting.

Horikawa’s enthusiasm was not dampened by the lighthearted turn, but it inspired another pivot, this time to the more modern clay figurines by Julene Mechler who created the menehune series in the ’50s and ’60s. “Look at these clay menehune, they are all unique. Mechler made each one by hand, and applied the glaze to each one, individually.” Indeed, there are no telltale similarities in any of Horikawa’s examples. “She produced these at her studio in Windward O‘ahu,” he says “and customers would drop in and ask for something specific and she would create it as a one-of-one for them.”

“So, I wanted to end on a less-serious note with Mechler and the slightly knick-knackish menehune, but it also plays an important part in predating much of what we see on shelves today.” This fortuitous peek at a fraction of a collection brought out the early nascent pieces that influenced much of today’s art, and with that, Horikawa glides us to the proverbial riverbank, where we step ashore and take halting steps on dry land, filled with the honor of having heard the stories behind some of Hawai‘i’s treasured icons.